In our last blog: ‘How organisations transform to agility’, we looked at case studies of those on their journeys to becoming agile. In this blog, also based on the latest research paper from the Agile Research Network (ARN), we will look at the challenges and resulting tensions those organisations encountered and the questions businesses can ask themselves before the transformation process begins to avoid or minimise these. The questions were developed using the lens of paradox theory.

The three organisations cited were all publicly-funded, not required to make a profit, based in the UK and employed 500 staff or more. They were all distinct from one another in terms of goals, customer types, governance and management structures, and types of operational units.

Case Study 1: Council

Council leaders encountered the following challenges:

1. Undergoing transformation while maintaining business as usual: This challenge gave rise to the tension of having to divide resources between these activities, thus increasing workloads. Leaders observed that: ‘a lot of things fell through the cracks’ and that: ‘we lost a lot of focus on the day to-day delivery’.

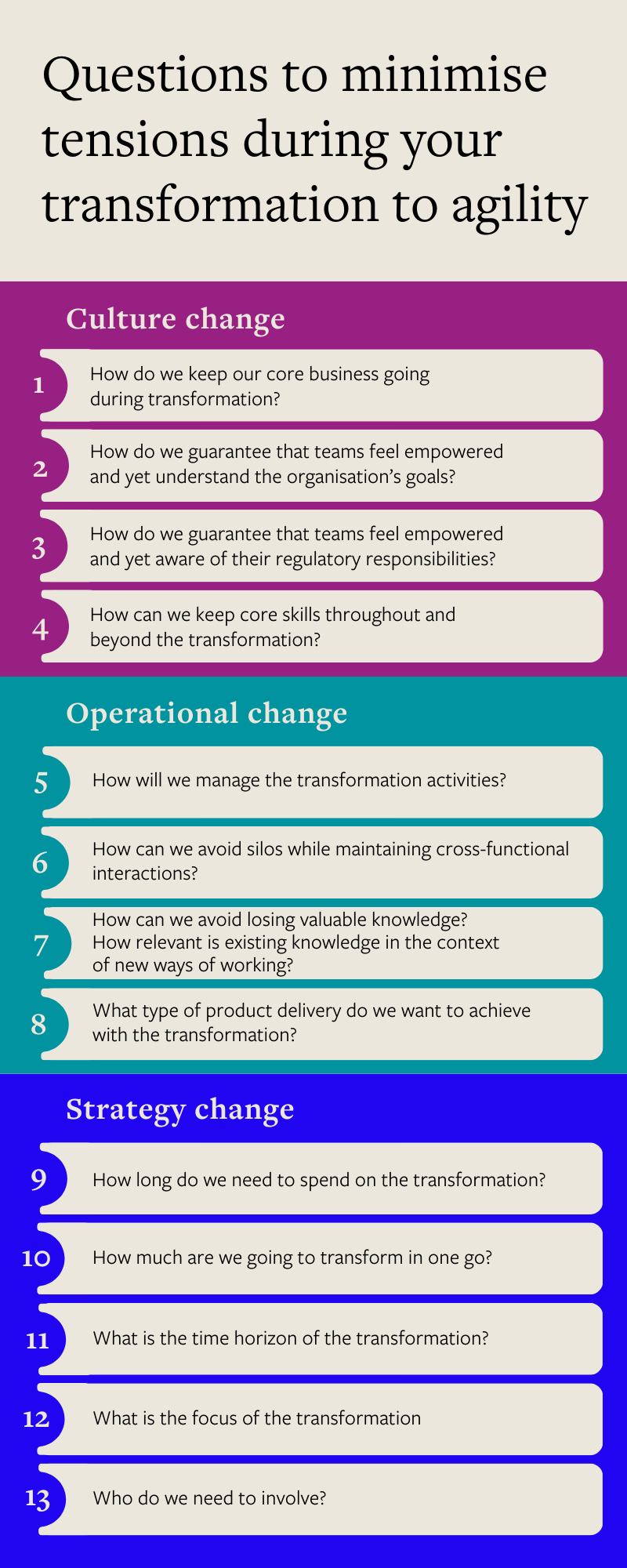

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How do we keep our core business going during transformation?’

2. Distributed authority while aligning with organisational goals: With authority distributed throughout the organisation, teams and staff felt empowered. However, a tension arose due to teams pursuing their own goals without checking that these aligned with organisational and other teams’ goals. Inter-team cooperation and some team based decisions were also not communicated appropriately.

There were concerns about brand consistency, and lack of a corporate plan making communications difficult and organisational priorities difficult to discern. Leaders worried that the ‘get on and do it’ attitude meant that processes and procedures weren’t being followed or were being created ‘on-the-fly’.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How do we guarantee that teams feel empowered and yet understand the organisation’s goals?’

3. Distributed authority while adhering to regulatory processes: Teams had the autonomy to make and act on decisions, but a tension arose when it became apparent not everyone was aware of, or following, regulatory processes when doing so. For example, one department attempted to handle waste management independently, but were unaware of relevant regulations. Resentment also arose when, after a period of people ‘doing their own thing’, they were then told what to do again.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How do we guarantee that teams feel empowered and yet aware of their regulatory responsibilities?’

4. Maintaining required skills as well as evidencing required new behaviours: As part of the council’s agile transformation, all staff underwent a behavioural assessment, with new recruits also being required to show evidence of these behaviours. The tension that arose was some staff with the right behaviours not having the right skills and vice-versa. Leaders observed for example that the most technically skilled people tended to be those most likely to not achieve the behaviours. The council therefore lost some staff with specific skills and found it harder to recruit people with both the required skills and commercially-minded behaviours.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How can we keep core skills throughout and beyond the transformation?

Case Study 2: University

The challenges for university leaders were:

1. Both top-down and bottom-up transformation: Both of these activities happening at the same time created a tension between the need to align senior management’s control - to promote and support agility, with the operational adoption of agile practices.

There were workshops to try to align top-down and bottom-up approaches and agile training courses for all staff were organised but these were over-subscribed. In addition, frontline staff were not engaged in agile working changes.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How will we manage the transformation activities?’

2. Functional silos versus cross-functional cooperation: Agility favours cross-functional cooperation but the university’s organisational structures and cultures were based on functional silos — in other words — production specialists, content providers, infrastructure and support units operating independently. The tension here was how much to structure and manage according to functional groupings and how much according to cross-functional teams.

The most acute problems were related to which agile methods to adopt, how to redefine old roles and define new ones and ensure empowerment of teams. There was resistance to collaboration across different departments, with some being concerned that ‘Scrum is a radically different way of organising from the university status quo and requires significant changes to governance, resourcing and roles’.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How can we avoid silos while maintaining cross-functional interactions?’

3. Maintaining knowledge while moving to new ways of working: A large amount of organisational knowledge was embedded in existing ways of working, with the concern that new ways of working and new terminology might override valuable experience. The tension was deciding how much existing organisational knowledge and experience needed to be kept when moving to new processes, and how to identify what was important enough to retain. There was concern that knowledge was not being leveraged due to lack of a repository of knowledge about how they did projects.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How can we avoid losing valuable knowledge? How relevant is existing knowledge in the context of new ways of working?’

4. One-shot delivery vs incremental product refinement: Traditionally, the university would deliver a complete course as a whole to the customer. A tension therefore arose during the transformation to agility as the agile way would require faster, incremental delivery in shorter iterations. The concern with this new method was that a cheaper and faster operational target would jeopardise the quality of the product and leaders were unsure exactly how much of the course should be delivered in one go.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘What type of product delivery do we want to achieve with the transformation?’

Case Study 3: Charity

For the charity, challenges were:

1. Avoiding changing too quickly or changing too slowly: The organisation needed to transform quickly enough to respond to environmental threats it faced while changing at a pace that a) allowed staff to adapt and b) allowed sufficient time for the changes to be accepted by the Board of Trustees, who worked to a structured timetable. The tension arose from trying to achieve this balance.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How long do we need to spend on the transformation?’

2. How much to change vs how much to keep stable: Changing too much at any one time can lead to instability. Evidence showed that leaders recognised the need to change how people worked and how they supported their customers but felt uneasy about continuous change and stability. The tension arose from deciding how much to change and how much to keep stable at one time.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘How much are we going to transform in one go?’

3. Change for the short-term vs change for the long-term: This tension emerged because immediate challenges needed a short-term response. Short-term changes however can compromise long-term goals. For example, significant financial cuts were needed in the short term, but long-term goals such as increasing the customer base required significant investment.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘What is the time horizon of the transformation?’

4. Change the strategy vs change the structure: The charity made extensive changes to the organisational structure prior to developing a new strategy. However, embedding an agile process to evolve the strategy iteratively required further changes to the organisational structure.

The tension was between letting the strategy development process lead structure change or changing the structure to accommodate an agile strategy development process. The agile approach’s collaborative way of working was counterculture to a traditional, hierarchical way of working with siloes.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘What is the focus of the transformation?’

5. Involving enthusiastic people to energise change or involving representatives from the whole organisation: Previous experience convinced the change managers that involving everyone from across the organisation would not be successful for initiating this transformation. Instead, they started with a small, self-selected and enthusiastic group. However, other colleagues felt undervalued because their input was not sought.

This tension concerns whether to initiate change through the participation of enthusiasts, thus risking that, due to the small size of this group, it may not have enough authority and capability to do so, or to do it through representation across the organisation, which risks a lack of the enthusiasm or ‘buy-in’ necessary for the change to be successful.

To minimise this tension, first ask: ‘Who do we need to involve?’

If you missed the earlier blog from Agile Research Network on you can read it here: How organisations transform to agility

You can read more about Paradox Theory here: Paradoxical Leadership and How It Can Help

Please note blogs reflect the opinions of their authors and do not necessarily reflect the recommendations or guidance of the Agile Business Consortium.